The Expansion of Administrators and the Decrease of Instructional Spending is Sabotaging Public Higher Education, and It’s Intentional

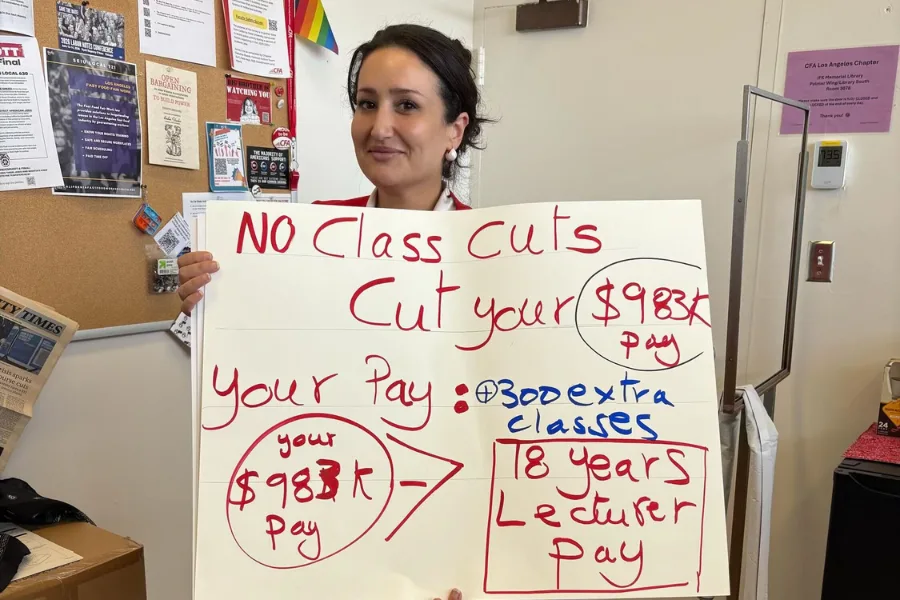

Amidst diminishing numbers of faculty in many departments across the CSU, the number of campus administrators has exploded to an astounding and disproportionate level. Moreover, the total compensation for many top-level administrators, or Management Personnel Plan (MPP) employees, has far outpaced those of full-time professors and lecturers over the past 15 years.

When the CSU Board of Trustees approved raising student tuition by 34% in 2023, they also approved administrative spending and salary increases.

By no means is this an accident, and it reveals a troubling blueprint of institutional priorities.

The rise of administrative spending, soaring student debt, and bleak working conditions of faculty are inextricably linked, and the phenomenon is harming our higher public education system.

So why is this happening?

There are a number of reasons, some more sensible than others.

Universities have always had their share of administrators, and for good reasons. They can help with student success, shape academic programs, develop policies, and manage incoming resources and finances. Roughly half a century ago, many administrators were drawn from faculty ranks, with faculty taking on part-time administrative roles with plans to return to full-time teaching and research. Under this framework, it was impossible for management to make moves without faculty consultation, given so many faculty wore administrative hats.

For that reason, faculty’s commitment to the university’s mission and values played—and continues to play—a crucial role in safeguarding public higher education as a public good.

Unfortunately, full-time professional administrators today are very unlikely to have any faculty experience. They know little about the needs of the faculty, students, and staff, and are indifferent to teaching and research. Instead, many view management not as a means for promoting the university’s mission, but as ambitions for expanding their roles within the university.

Consider just how many administrative titles there are nowadays: vice presidents, associate vice presidents, assistant vice presidents, provosts, associate vice provosts, assistant provosts, deans, and so on. Management believes the key to solving problems they’ve perpetuated is to hire more administrators.

But administrative bloat, or the expansion of the administrative class, has not improved the quality of education. Except for the administrators themselves, no one has called for more administrators. Students, faculty, staff, and community members have been adamantly opposed to the unwelcome growth.

At Sonoma State, MPP salary and benefits have risen to equal what the campus receives in tuition per full-time equivalent student (See Figure 1).

What makes even less sense is that—despite having more highly paid managers than ever before—management increasingly relies on expensive outside consultation. From 2019 through 2024, the Chancellor’s Office has awarded nearly 225 consulting contracts totaling $16.3 million, a number that does not include consulting contracts awarded by individual campuses, and which has grown even more in 2025.

Non-instructional costs have ballooned, and executive salaries are in large part to blame. The number of administrators hired on by other CSU administrators and their exorbitant salaries have led to the rise in tuition and student fees, which have grown at an even faster rate than the astronomical costs of medical services, child care, and housing. Students have taken on more debt to pay for their tuition and fees.

Much of this debt is structured around racial and gender lines.

As scholar Jalil Mustaffa Bishop points out, “Systemic lack of alternatives forces both Black people and Black institutions to rely on student loans, even to fight to preserve the policy… Across higher education, Black students experience this student debt trap coupled with primary access to institutions with low persistence and graduate rates. When they exit higher education with or without a degree, they face higher underemployment and unemployment rates along with lower pay for the same work as their White counterparts.”

The problem is compounded when we consider management’s trend of hiring less and less tenure-line faculty. Today, nearly 60% of CSU faculty are adjuncts or what management refers to as “temporary faculty.” These are part-time instructors who hold no long-term job security. Many teach anxiously from semester to semester, hoping to maintain enough classes to qualify for medical benefits for themselves and their families.

This shift away from tenure-line faculty has serious consequences for the quality of education. Many faculty are forced to work multiple jobs just to make ends meet, leaving them with less time to support their students. The impact is magnified even more when we consider the gutting of instructional resources. Course sizes increase, programs close, and faculty jobs disappear.

As students pay more, they’re met with far less meaningful engagement with faculty. In turn, faculty are left with the heavy burden of offering instruction under impossible conditions. Meanwhile, management continues its expansion, profiting off the backs of students and faculty and shortchanging them both.

What we get, then, are two very different stories from management about the CSU’s financial health. On the one hand, investors, creditors, and lenders are all told that the CSU is a booming business venture with record revenues. On the other hand, faculty, students, and staff are told that the CSU is a wasteland, completely depleted of resources, and that jobs and programs must be sacrificed to preserve what is left.

One of these stories has a false narrative.

Regardless, what we need is a permanent shift in organizational priorities and investment into instructional spending. While administrators have their place in our educational ecosystem, their growth has gone unchecked—even in the face of sharp criticism from a state audit report. They’ve built a framework that extracts from students rather than supports them, then abandons them to their debts once they’ve served their purpose.

Join California Faculty Association

Join thousands of instructional faculty, librarians, counselors, and coaches to protect academic freedom, faculty rights, safe workplaces, higher education, student learning, and fight for racial and social justice.